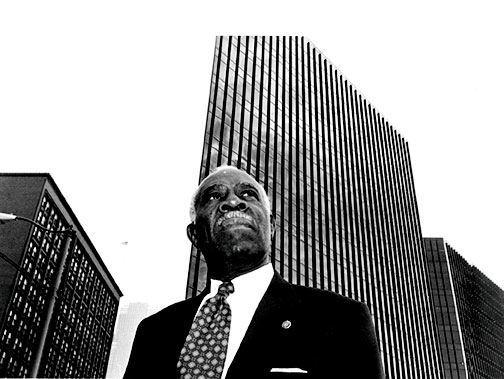

Robert Madison’s rise to the top of his profession as an architect began in the Jim Crow era. But the obstructions and insults merely sharpened his courage and determination.

By Rory O’Connor

“Whoever heard of a black architect?”

“Whoever heard of a black architect?”

Bob Madison’s rhetorical question comes in the middle of conversation we’re having about his storied career and the obstacles he had to overcome. As an African American born in 1923, there were plenty. His question refers to the mid-1950s, when he opened his firm, Robert P. Madison Architect on East 105th Street, and couldn’t find work. Real work designing real buildings.

“We did porches, basements, things like that.”

We’re in Madison’s Shaker Heights condominium, where he lives by himself with help from a housekeeper-cook. His wife of 62 years, Leatrice, died in 2012. His spacious unit at The Diplomat is decorated with abstract art, oriental rugs, and midcentury modern Scandinavian furniture, including a womb chair by Eero Saarinen.

Looking across his living room at his numerous awards, lined up on a shelf, it’s hard to imagine Madison designing porches to make a living.

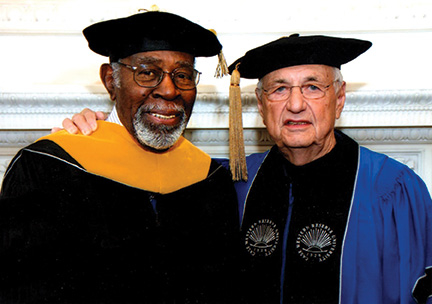

Madison’s honors and awards are legion. He was elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects (AIA) in 1974, one of its top honors, and 10 years later was elected the AIA’s Chairman of the Jury of Fellows. He received the AIA Ohio’s Gold Medal Firm Award, an honorary Doctor of Humane Letters from Cleveland State University and Kent State University, an honorary Doctor of Science degree from Case Western Reserve University, the Cleveland Arts Prize, and an honorary Doctor of Humanities from Howard University, where he studied as a young man and later taught.

Most recently, Derek Morton, a filmmaker from Washington, D.C., made a documentary about him, “Deeds Not Words,” which screened at the Greater Cleveland Urban Film Festival last September. The movie was five years in the making, off and on, the brainchild of his daughter Juliette, who lives in Washington.

Why all the fuss? First of all, Bob Madison is smart, funny, and charming. “He has a great talent for talking to people and getting them to listen, and for listening to them. He knows how to make friends,” says his long-time friend Philmore Hart. “He has a flair for life.”

But more to the point, Madison, now 95, has always been a man on fire, confronting and defeating racism where he found it (which was everywhere) mostly by mocking it or ignoring it, from his time in the 92nd Infantry Division in World War II – the segregated “Buffalo Soldiers” – whose commander, Major General Ned Almond, wanted nothing to do with them, to his time at Western Reserve University’s School of Architecture in the late 1940s under a dean who shunned him as a “colored boy.” The dean asked him sarcastically upon graduation, “What will you do now, work in a lumber yard?”

Right. Who ever heard of a black architect? The fact that he later found a tolerance of his skin color and an appreciation of his skills under Walter Gropius at Harvard and at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris as a Fulbright Scholar still didn’t mitigate the question when he started his own firm.

In the end, all the fuss is about courage and determination, even more than architecture.

The Scheme

Madison was born in Cleveland and grew up with three brothers, Julian, Bernard, and Stanley, sons of a civil engineer, Robert senior, and a mother, Nettie, who encouraged their sons from the start of their lives to pursue professional degrees. In the documentary film, Madison says his mother “had the scheme” for him to be an architect when he was in first grade.

Not long after Madison was born, Robert Sr. took a job teaching chemistry at Selma University in Alabama for several years, then moved on to Columbia, South Carolina, then Washington D.C.

When the Great Depression hit, the family suffered like most Americans, primarily because the engineering firms for which the father was eminently qualified refused to hire blacks. “Dad was overqualified, as a matter of fact,” says Madison.

The family eventually returned to Cleveland, where Bob graduated from East Technical High School. Having been prodded by his parents, he was studying architecture at Howard University in Washington when the U.S. entered World War II. Being a ROTC cadet, he was in uniform by 1943, training at Fort Benning at Columbus, Georgia, then Fort Huachuca, near Tucson, Arizona. He graduated as a second lieutenant.

“All officers above the rank of first lieutenant were white because no white man would salute a black man.” Army policy.

In a 2012 radio interview on WJCU, the John Carroll University station, Madison told interviewer Yemi Akande that the 17 weeks of training at Fort Benning with other black soldiers “was not a comfortable experience,” not because of the rigors, but because of the racism. “But we expected it. It wasn’t new.”

In Arizona, the division was trained for the Italian Campaign. “No other state would have us,” Madison told Akande. “We were 20,000 [black] men with guns.” (Actually, from 1913 to 1933, Fort Huachuca was headquarters for the original Buffalo Soldiers, the 10th Cavalry Regiment, which was formed in 1866 to fight in the Indian Wars. The nickname was given to the soldiers by Native Americans, who likened the soldiers’ hair to a buffalo’s.)

After Huachuca, they were put on a train that rolled through the deep south on its way to the troop ships at Hampton Roads, Virginia. People threw rocks and spit at them.

In Italy, Madison won the Purple Heart and several battle ribbons. “And the people cheered us. Those people cheered us, while people in the U.S. spit at us.” He grins, savoring the irony.

When he returned to Cleveland after the war, he decided to continue his architectural studies at what was then Western Reserve University, prior to its merger with Case Institute of Technology. When he applied, the dean, Francis Bacon, flatly turned him down because of his color. As Madison says, WRU “didn’t have enough black men to make up a basketball team.”

Madison was undaunted. “I went home, put on my uniform with my Purple Heart and battle ribbons, and went to the dean of admissions, not to Bacon. I showed him my work from Howard. This was 1946. So they tested me. “I got admitted, but they gave me ‘flunk-out’ classes” – particularly in physics, meant to be so difficult that he could not possibly pass them.

Pass them he did; that is, those he was allowed to take. He was awarded a bachelor’s degree without finishing all the necessary coursework – that was how badly the administration wanted him gone.

Cognac and Cigars

Still, his time at WRU had its upside in that he made some friends. Retired Cleveland architect Philmore Hart was a fellow student. Hart had grown up in the Jewish section of Glenville and understood the impact of bigotry.

Madison tells this story: In the summer of 1947, Madison went to a party for graduating seniors in architecture at the Lakeshore Country Club (now the Shoreby Club) in Bratenahl. He was soon confronted by the president of the class of ’47 and a few other students. Bacon and the club manager were also in the posse. The group told Madison the club did not serve “coloreds” in the dining room, but he could eat in the kitchen with the help, or take the meal home with him, or be given his money back – $25.

“I listened incredulously,” Madison says. Enter Phil Hart, who had overheard the discussion. Hart announced, “If Bob doesn’t eat here, I don’t eat here. And if I don’t eat here, nobody eats here.”

Hart, now 96, lives at an assisted living facility in Beachwood. He clearly remembers the incident. “That’s exactly what I said, and I could say it because I had money. They let Bob sit down and eat with the rest of us, but they asked him to leave when he was finished, which he did. There were many similar incidents at school involving Bob. That dean was a jerk, a real jerk.” (Ironically, Hart eventually became chairman of the Department of Architecture at CWRU. And more irony: Years later, after Madison started his practice, Bacon invited him and his wife Leatrice to his Shaker home for dinner to congratulate him on his success.)

Hart and Madison are the last of their contemporaries. “Though after Bob came back from Harvard we spoke different languages, architecturally speaking,” Hart says. “He studied under Gropius. I studied under Mies van der Rohe at the Illinois Institute of Technology. But that’s the way architects are. We disagree.”

Another friend was Robert Andrews Little, who taught design at Western Reserve’s architectural school and had started Little & Associates. Little was a true blueblood, born in Boston, a direct descendant of Paul Revere. He was married to Ann Halle of the Cleveland department store family and eventually became one of Cleveland’s preeminent architects. He was a proponent of the Bauhaus School, having studied at Harvard under Gropius.

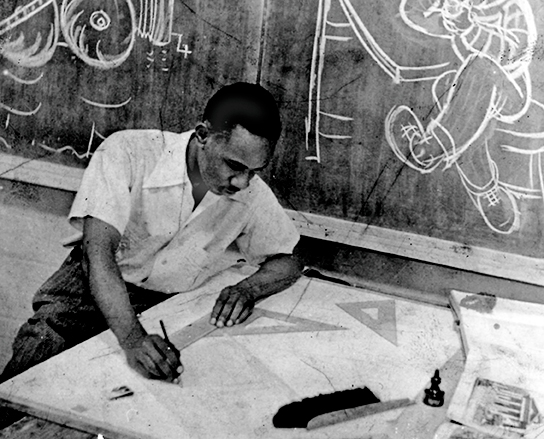

Little was to be a huge influence on Madison’s own career. After he was graduated from WRU in 1948, Madison went looking for work at Cleveland’s major firms only to be told the same old “no coloreds” story. Finally, he went to see Little, volunteering to work free for two weeks so that Little could see what he was capable of. Little hired him, a major turning point in Madison’s career.

When Madison joined Little & Associates, the company had not yet attained its status as one of Cleveland’s go-to architecture firms. That was a year or two away, and Little himself was still a relative newcomer to Cleveland. Nor had Madison yet taken the state exams for registration as an architect. But the job offered him a working education, a practicum for all intents and purposes, while he studied for the state exams.

He still had to contend with the racist norms of the era. He wasn’t welcome at the restaurants the rest of the staff frequented at lunch, so he brown-bagged it. But, just like at WRU, that path led to another life-long friendship. Another Little employee, a designer named Mort Epstein, saw what Madison was going through and also started bringing his lunch to the office. The two would play chess during lunch break and they became close. Epstein would go on to found Epstein Szilagyi Designers, now Epstein Design Partners, and become a passionate supporter of the Ohio American Civil Liberties Union.

Epstein died in November 2013. Christine Link, the executive director of the Ohio ACLU at the time, addressed the crowd at Epstein’s memorial service. “At a recent birthday party…I listened to Mort and Bob Madison talk about their early days as friends together in Cleveland. Bob faced a great deal of struggle breaking into his chosen field. A simple office lunch or dinner downtown with Bob could become a tense experience when ignorance produced insults or rudeness. Mort was often there to stand with Bob, supporting him and being proud to be with him.”

Madison in the meantime had married Leatrice Branch, a teacher, and sat for the state exams in Columbus with Phil Hart. The exams lasted five days. He passed on his first try, a rarity. Only two others in his group managed to do it. Robert P. Madison was the first registered African-American architect in Ohio. Robert Little treated the office to cognac and cigars.

Connections

Leatrice had a master’s degree in teaching — at the time called Educational Guidance. She urged Bob to get a master’s as well. And why not? The G.I. Bill, signed into law in 1944, would pay the tuition, as it had at WRU. For a vast number of World War II veterans, black and white, the G.I. Bill was their ticket to success. Millions of veterans used it for higher education and job training programs. It created the largest prosperous middle class America had ever seen.

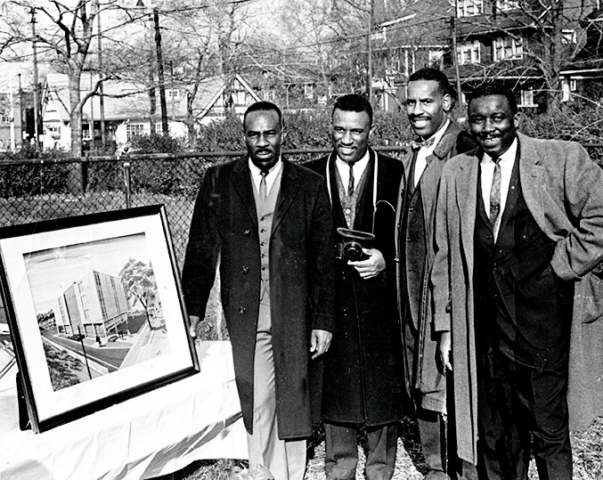

By early 1951, Madison was at Harvard with Walter Gropius. He finished a year later, and returned to Howard University to teach. While he was there, he was awarded a Fulbright Scholarship to study at École des Beaux-Arts in Paris for a year. He and Leatrice returned to Howard for a brief time, then came back to Cleveland, where he opened his practice. There was no real work forthcoming until another group of African-American professionals who were shunned by their white counterparts approached him. Madison accepted a commission from a group of black doctors who were routinely denied office space, and the Mount Pleasant Medical Center at East 139th Street and Kinsman Road came into being in 1957. The building won an American Institute of Architects design award.

That was followed by the Medical Association Building at East 105th Street and Ashbury Avenue, near the Cleveland Cultural Gardens, and a commission from the AME Church — the first Protestant denomination to be founded by blacks — to be its official architect. Madison built AME churches across the country.

When Carl Stokes was elected mayor of Cleveland in 1967, “that’s when things really opened up,” Madison says. Stokes was one of the first two black mayors of major American cities. The other was Richard Hatcher of Gary, Indiana, elected at the same time as Stokes. Their elections broke ground for black community leaders to win mayoral elections across America.

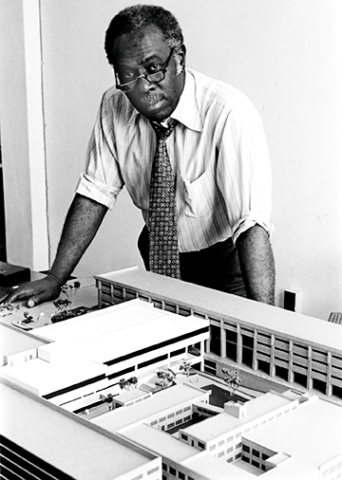

Madison’s brother Julian, a civil engineer like his father, knew Hatcher. Another friend of Julian’s was Kenneth Gibson, elected mayor of Newark, New Jersey in 1970. Madison & Madison International, as the firm was now called, got commissions from both Hatcher and Gibson, and even opened an office in Gary. Maynard Jackson, elected mayor of Atlanta in 1973, commissioned the firm to work on Atlanta Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport. That connection came from both being members of the influential black fraternity Alpha Phi Alpha, of which many of America’s most prominent black political leaders and artists were members, including Martin Luther King, Jr., Duke Ellington, W.E.B Dubois, and Thurgood Marshall.

Of course there was much more to it than making use of connections. “There was painstaking preparation, and arduous hours in demonstrating our skills to an eager clientele. I am good at what I do,” Madison says behind his boyish grin.

One has only to visit the firm’s website at rpmadison.com to see the list of projects the firm has been involved with in Greater Cleveland alone, including the Cleveland Public Library, the Downtown Hilton Hotel, the Cleveland Museum of Art, the Cleveland Museum of Natural History, Quicken Loans Arena, Cleveland Browns Stadium, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and Museum, and the Great Lakes Science Center. Yet his proudest achievement is the American embassy in Dakar, Senegal — “the port city where my ancestors came from.”

Madison finally retired in 2016 at the age of 93. He sold the firm — now called Robert P. Madison International — to three of his employees, including his nephew Kevin, Kevin’s wife Sandra, and Robert Klann. Sandra is the majority owner, and today the firm is the largest black female-owned architecture firm in Ohio.

Who ever heard of a black architect? In 21st century Northeast Ohio, pretty much anyone who matters.