A Moral Obligation

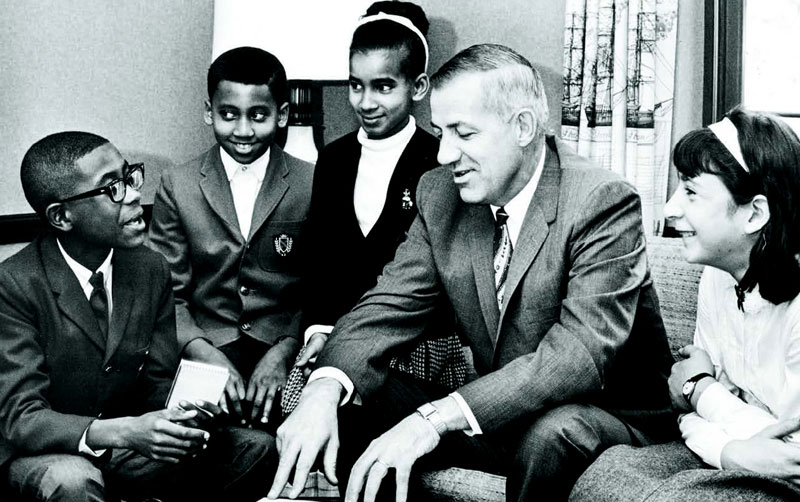

Dr. John H. (Jack) Lawson was superintendent of the Shaker schools from 1965–1976. Here, he recalls the landmark voluntary racial integration program in the Shaker Schools, known as the Shaker Schools Plan, which began during his tenure.

His children, John, Paula, and Jay Peter, all graduated from the Shaker Schools. Lawson later went on to become the Massachusetts commissioner of education and vice president at the University of New Hampshire. He is now retired and lives in Florida.

One of the reasons I was interested in moving to Shaker Heights was that I wanted my children to have the opportunity to get to know students of all races, all religions, all ethnic groups, all political groups, all economic groups. That’s the way it should be in a democracy. When I arrived in 1965, about 16 percent of our students were African American, and during my time there that increased to about 36 percent. However, Moreland Elementary School reached a point where about 98 percent of their students were African American. When we reviewed the test results as we did every year, I noted that our Moreland students were at the bottom. (Moreland was repurposed as the Shaker Heights Public Library after several elementary schools were closed in the late 1980s.)

It was my perception then, and it always has been, that a school district has the moral obligation to provide the best possible education for all students. We weren’t providing the best education for some of our minority students because they were isolated. The research at that time was very clear: If you isolate a group of any type of individuals from the mainstream then they aren’t going to have the same kind of opportunity. I thought it would be wrong to just continue doing what we were doing, which is why we decided to make a change.

We had an informational meeting about voluntary integration at the High School, filling the auditorium. Bob Rawson was the head of the school board at this time, and after he introduced me at the meeting, a number of people booed, and they went on for a while until they finally quieted down. We answered all their questions until 11 pm that night.

“It was my perception then, and it always has been, that a school district has the moral obligation to provide the best possible education for all students. We weren’t providing the best education for some of our minority students because they were isolated.”

The major objection people had was that they thought their property values would go down. Also some of the people thought it was going to be costly because of the extra busing, but we were able to get a grant from the Ford Foundation to cover those expenses.

We held a number of meetings at the elementary schools, and some people were for it and some disagreed. I think I received about 200 or so letters from residents who were against trying to integrate the schools, and there were a lot of telephone calls. On the other hand, we had great support from the PTA committees and the various church leaders and community associations.

In the meantime, a group of citizens who were interested in integration sent me a petition saying that they would be willing to volunteer their children to attend Moreland School, so we built that into the Shaker Plan. We then had several African-American families volunteer to send their students to the other elementary schools. That gave us a better racial balance at each school.

The first day of school when we implemented the Shaker Plan [in the fall of 1970], we had an administrator from central office on each one of the buses to make sure everything went smoothly. One of the major networks came and took pictures of what was going on and they ran it on the television that night. After that, I didn’t get any more telephone calls and we didn’t have a single problem.

After we integrated the elementary schools, we did the same for the two junior highs. When we looked at test scores in the following years, the achievement of black students had increased significantly, and there was almost no difference between white and black students’ scores.

A few years after we integrated, a study of the property values for all of the communities in Cuyahoga County came out, and despite what people were worried would happen, the properties in Shaker Heights appreciated higher than in all the other communities.

A number of residents later told me, “Initially, we really didn’t favor what you were doing, Jack, but now we support it because our children are doing well and they are happy. They’ve met students they otherwise never would have met.”